University Partnership Research Project

Herstory.York and York Museums Trust (YMT) have a research partnership with the University of York. In 2022 we co-produced the 100 Changemakers exhibition at York Castle Museum to showcase Herstory.York’s research and connect them to YMT’s collections. We piloted a research project with the university looking at Victorian Women which is now an annual project for the students. In 2023-24 we worked with BA History students on an assignment to research 10 ‘complicated’ stories of women. They uncovered stories of mental health, same sex love, crime and poverty. You can read all of the partnership’s research below.

Mary Ann Felgate (sometimes spelt Mary Anne Felgate) was born in 1839, and worked at the Retreat, previously known as the Friends Asylum for the Insane, as a lady’s companion. She was born in London, and lived in Paddington, Middlesex, and Kensington during her lifetime. Mary moved to Walmgate, York during the 1880s. The asylum was one of the first in the world that believed psychiatric patients should not be mistreated; Mary Ann’s role was vital for this process as her role encouraged patients to feel comfortable and at home during their stay. Mary was not a nurse; instead, she provided the patients with comfort and support, and was one of the two women responsible for this role within the Retreat. During her time at the asylum, a number of new buildings were constructed and the hospital expanded widely.

Download Mary Ann’s research sheet here

Download Mary Ann’s presentation here

Lucy Sturdy (b.1860) is just one woman among many who was disenfranchised by a system of crime and poverty in 19th century York. At the age of 14, poverty forced Lucy to steal for survival, trapping her into a cycle of crime and by 1885, she had already been arrested four times. A child-bride, this was only made more inherent when Lucy had her first-born aged 15. By 1885, aged 25, Lucy was declared unfit to plead due to insanity after being caught for stealing a coat and a postal order and was committed to Clifton Hospital. Lucy only spent one month in the prison; she stole the keys, escaped under the cover of night and seemingly disappeared from the records. Lucy’s story is one of hardship and survival, a narrative not uncommon for working-class women in Victorian York. Trapped in a cycle of crime and survival, Lucy is just one victim in a wider historical trend.

Download the research sheet here

Download Lucy’s presentation here

Mary Stubbs was a plaintiff in a sexual slander case that took place in the court in York. She sued a man named Israel Bradley for sexual slander after he called her a ‘bloody thundering whore’ and claimed that he had ‘connection with her in every part of the house even in the cellar’ outside of the Bay Horse Inn on Blossom Street. The case occurred between 1841 — 28/7/1842. Bradley was given the full fine which he was unable to pay and therefore was imprisoned.

Mary married Samuel Stubbs in 1839 in Knaresborough, who later became the innkeeper at the Bay Horse Inn. At the time of the case she had been married for 2 years. There is no evidence that she had any children and she and her husband are seen living alone in the 1881 census. She died in York in 1888 at the age of 75.

Download Mary’s presentation here

At 27 years old Gertrude Watson was admitted to the Retreat on request of her father even though there was ‘no mental or bodily disorder’.

The Retreat pioneered a seemingly revolutionary approach to mental health treatment in the Victorian era. This approach was known as moral treatment; it was seen to be more humane. Gertrude’s case is interesting as it highlights a more problematic side to moral management. Why was she being held despite lack of symptoms and this being questioned at the time? Rising concern at the time about wrongful confinement in private asylums contextualises the potential immorality of Gertrude’s confinement.

Evidence The Office of Commissioner’s concern for the justification of her confinement suggests that Gertrude’s confinement could have been wrongful. R. Baker’s response highlights the power medical men had over patients. The focus was on the request of Gertrude’s father, not Gertrude’s mental state.

Download Gertrude’s research notes here

Sarah Smithson belonged to the middle-upper classes of York who helped propel the cause of Women’s Suffrage through political connections and their education status. Sarah was secretary of the York Women’s Liberal Association, and Worked for the Ladies Education Committee, as secretary for the “Ladies lectures,” a group that pioneered the education of adult women who had otherwise lost out on the opportunities of higher education

In 1877, five awards handed out to women by the Cobden Club, a London based academic “gentlemen’s club” in recognition of the most successful students of political economy in connection with the Cambridge University wider lecture syndicate, Sarah Smithson was one of these women.

Alongside her husband, and Joseph Rowntree, Smithson petitioned for education rates in schools to be lowered, as well as against the domination of the church over education. She became a notable member of York high society, often reported as in attendance of various liberal meetings and events, in the company of J. S. Rowntree.

Download Sarah’s research notes here

Download Sarah’s presentation here

Content warning – suicide and mental health

Anne Robinson was born in 1834 in North Yorkshire. In 1857 Anne married Richard Robinson, a watchmaker and subsequently moved to Sheffield. In 1858 Anne gave birth to their daughter Annie, followed by two sons, Herbert and Edgar. Sometime after their marriage her husband Richard took over his father’s watchmaking business and Anne is registered on the census records as a ‘watchmaker’s wife’. Anne then, for a while, lived a comfortable life as a middle-class woman, which would have involved running her house. However, newspaper reports suggest there were continuous money issues for Richard’s business leading to bankruptcy in the 1870s, which appears to have been a major factor in Anne’s deteriorating mental health and eventual treatment at the Retreat hospital.

Anne’s story shows how misogyny affected the treatment of women in asylums. She was admitted in December 1892 and whilst there she was deemed to be depressed and suicidal. In the patient notes Anne repeatedly worries over her husband’s financial state, anxious that he cannot afford for her to stay and receive treatment at the hospital. However, her concerns were repeatedly dismissed as “ramblings” by the staff. In February 1893 Anne was discharged and said to have been mentally improved, only becoming depressed occasionally. However, in April 1893 Anne committed suicide through deliberate consumption of carbolic acid at her home in Sheffield. The Jury’s verdict was that she had committed suicide whilst in a state of temporary insanity suggesting that the Retreat’s medical care had not been sufficient.

Download Anne’s research notes here

Content warning – racism and mental health

“Oh that I had some friend at my side to fight amidst this mortal warfare in my defence, but I have not even that” – Eliza Raine, 1812

Eliza Raine and her sister Jane were born in India in 1791 under British Imperial rule to an Indian mother and a British naval surgeon. At the age of 12, the girls were taken on the long journey to England, out of the care of her mother whom they never saw again. They were under the guardianship of William Duffin, a close friend of her fathers.

She went to school at Kings Manor boarding house in York where she met Anne Lister, who wrote detailed diary entries about her life and romantic relationships, and is thought of by some as Britain’s first “modern lesbian”. Eliza and Anne lived in the same room, developed a close, loving relationship and wrote many love letters, notes and poems to each other; Eliza would stay with the Lister family during the summers. However, by 1810 their relationship had become distant; Anne was living in York and Eliza was living with Lady Crawford, who she did not like, in Doncaster.

In 1816, Eliza’s mental health was considered to be in decline and she moved into a private asylum in Clifton. She died alone aged 69, having spent roughly 44 years in asylums. Her letters to Anne, writing and poems during this period often describe feelings of longing and loneliness, probably due to her mixed race and her sexual identity, making her isolated as an outcast in society. She therefore has a unique and important story to tell in the history of women in York.

Download Eliza’s research notes here

Content Warning – violence and domestic abuse

Jane Fowler was a York resident who lived in the notoriously poor area of Walmgate, she struggled with alcoholism and in March 1856 she was convicted for the manslaughter of her adult daughter, Jane Rylatt. Jane and her daughter had an immensely strained relationship as they argued constantly and witnesses claimed to have seen Mrs Fowler abuse Mrs Rylatt. Jane Rylatt was left to bleed out from a neck wound for 13 hours before any medical assistance was called. When questioned about her daughter’s injury, Mrs Fowler was inconsistent with her explanation, claiming that Jane Rylatt had fallen on a shovel, a coal hole and a kettle. When questioned about why Mrs Rylatt was left so long without medical attention or her husband being notified, Jane Fowler said that her daughter had begged her not to get anyone. The trial that followed Jane’s death found that Mrs Rylatt had been stabbed in the neck with a knife that was found in the Fowler residence, stained with blood. The Jury decided that the crime had not been premeditated and she was convicted of Manslaughter. When Mrs Fowler heard about the conviction she reportedly became hysterical. Mrs Fowler spent one week in jail and then went on to look after Jane Rylatt’s child, her granddaughter. Jane Fowler’s story is one of strained familial relationships in a condensed and impoverished area, her propensity for alcohol combined with this tells a very dark and tragic tale of how these circumstances can have fatal results.

Download Jane’s research notes here

Born in York on the 15th September 182611 to Isabella and Joseph Hick, Mary Ann Craven went on to run a successful confectionery company until her death on the 31st July 1900. After becoming a widow at thirty-three (1862), she had three children and a full time business to run. She was an admirably formidable woman – rumoured be “stronger” than her husband – who merged two major companies so successfully that she was in a position to purchase a notably large house in the 1870s on Heworth Green. Despite her hardships, she was a “wonderful little old lady” who frequently participated in charity work; visiting “sick workers with blankets, clothing and food.”

Download Mary Ann’s research sheet here

Download Mary Ann’s presentation here

Annie Coultate‘s (b.1856) role as part of the vanguard, along with Violet Key-Jones, in the establishment of the WSPU in York – the support of her family on this political matter is suggested by their boycotting of the 1911 census – Annie indicates the network of political activism within the community in York

Her role as a professional throughout her adult life, progressing from the 19th into the early 20th century, despite the expectations placed upon women to remain in the house after marriage/having children – Annie shows the traits of tenacity and determination that are admirable in any woman today.

Download Annie’s presentation here

Sarah Smithson belonged to the middle-upper classes of York who helped propel the cause of Women’s Suffrage through political connections and their education status. Sarah was secretary of the York Women’s Liberal Association, and Worked for the Ladies Education Committee, as secretary for the “Ladies lectures,” a group that pioneered the education of adult women who had otherwise lost out on the opportunities of higher education

In 1877, five awards handed out to women by the Cobden Club, a London based academic “gentlemen’s club” in recognition of the most successful students of political economy in connection with the Cambridge University wider lecture syndicate, Sarah Smithson was one of these women.

Alongside her husband, and Joseph Rowntree, Smithson petitioned for education rates in schools to be lowered, as well as against the domination of the church over education. She became a notable member of York high society, often reported as in attendance of various liberal meetings and events, in the company of J. S. Rowntree.

Download Sarah’s research notes here

Download Sarah’s presentation here

Ann Swaine was a British writer, suffragist and philanthropist concerned with improving higher education for women; she has been described as “an active, clear-thinking woman who divided her time between philanthropy, feminism, publishing, translation, and domestic and familial duties

Swaine was one of the first three women in York known to have lent their names to the women’s suffrage campaign (along with Emma Fitch and Agnes Smith) as part of the first mass women’s suffrage petition presented to the Commons in June 1866.

Her father, Edward Swaine advocated universal manhood suffrage but for “the exclusion of women and others from the franchise” because he felt that it was “not conceivable that the condition of women… would be improved by their admission to a personal voice in the legislation of the country.

She wrote a collection of short biographies called ‘Remarkable Women as Examples for Girls’ for the Sunday School Association that was published in January 1882.

Download Ann’s research sheet here

Download Ann’s presentation here

The York suffrage movement has been quite well documented in the city, taking shape in the form of a community play and research undertaken by the York Castle Museum. When we think of the opposition to the movement, often think of misogynistic men. However, it would be interesting to challenge our collective memory by acknowledging the role of seemingly ‘unfeminist’ female anti-suffrage activists.

As a wealthy, powerful and independent woman, Edith Milner could be considered a prime candidate for the Suffrage Movement. However, Edith’s involvement with the York’s Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WNASL) is insightful in showing how anti-suffrage is not necessarily connected to anti-feminism.

Additionally, Edith Milner encapsulates the inherent tension within the anti-suffrage movement. As Bush asserts there is an “implied contradiction between women’s public campaigning for anti-suffrage and their advocacy of a quieter, more domestic role for women”.

Download Edith’s research notes here

Download Edith’s presentation here

Hannah Hodgkinson was born in 1869 in Stockport and first came to York in August 1884 as a student of the Quaker School, the Mount School. While Hannah was at Mount School a handful of female Quakers began attending university after the University Act of 1871.

Between the years 1885 to 1886, Hannah kept a diary where she would detail her classes, what it was like to board at the school, as well as personal interests. It becomes apparent through reading her diary that Hannah was an avid reader taking inspiration from American novels; What Katy did at School and Gypsy Breynton. These texts were not the typical Quaker texts of the time and featured unconventional, tomboy-ish heroines, and so Hannah would read them with her friends away from the prying eyes of their teachers. This ‘secret book-club’ was later named ‘The League of the Jolly-cum-profs.’

Her diary concludes on the 22nd June 1886 when she scrawled in her diary “LEFT SCHOOL THE END”. What we do know of Hannah, is that after leaving the Mount, Hannah did not marry nor have any children. This is most unusual for Quaker women during the nineteenth-century and may signify a possible LGBTQ+ representation but at the very least a woman who chose not to conform to traditional social conventions and expectations in the nineteenth to early twentieth-century.

Download Hannah’s research notes here

Content warning – self harm, abuse and mental health

Eliza Emma Reed was a mother, daughter, wife and sister born in Rudston in 1851. Daughter to Margarett and James Agars, Eliza became affiliated with York’s dark history when she was admitted to the Retreat on May 14 1893 on account of her acute melancholia (depression) and violent outbursts. Eliza’s husband, Walter John Reed, consented to her admittance, leaving their three children, Clarice Annie, Ethel Margaret, and Hilda Gertrude, in his sole care.

Opening in 1796, York’s Retreat advocated for a more humane approach to mental health treatment, rejecting the use of fear to control patients, instead allowing them as much freedom as possible. However, on only her second day at the Retreat, Eliza, sadly, attempted to take her own life. From this point on, Eliza was kept under mechanical restraint (in a straitjacket) to prevent her from inflicting further self-harm. This inhumane approach to mental illness is something that must be discussed and reflected upon.

Stories like that of Eliza Emma Reed are vital to our understanding of women’s history in York; though it is important to celebrate change-makers and glass-ceiling breakers, we must also recognise the existence of women who deserved so much better than what they got. Eliza died on January 27 1894 of pneumonia. She was so close to being formally discharged from the Retreat, going so far as to take a leave of absence at home with her family merely a month before. Unfortunately, Eliza fell ill before getting the chance to rewrite her story.

Download Eliza’s research notes here

Content warning – child loss and mental health

Hannah Mills was a mother of five children. She spent the majority of her life in Leeds but the crux of her story takes place in York. She was married to Samuel Mills, a stuff-maker in Hunslet Carr.

In March 1786 Hannah lost her husband – this loss was compounded by becoming a pregnant single mother and widow, who would go on to lose three of her children, including her youngest within the space of two and a half years. This induced a period of deep melancholy, during which she sought help and found solace in the Quaker community, who would often provide for those in need – both financially and spiritually.

Consequently, in March 1790, Hannah was admitted to the York Insane Asylum, now Bootham Park Hospital. This was renowned for having very poor conditions, with patients regularly experiencing neglect and abuse. Whilst the records were lost to a fire during an investigation in the early 1810s, it is likely that Hannah would have witnessed or perhaps even suffered herself.

The Quakers in Leeds financed both her confinement and her children’s future welfare and made unsuccessful attempts to contact and visit her through the Friends of York. In response to her death, just six weeks after her admittance, the Tukes (a prominent Quaker family in York) proposed The Retreat as a safe haven for Quakers struggling with mental health. Despite the pioneering mental health treatment ideas, Hannah Mills is rarely mentioned outside of a footnote.

Download Hannah’s research notes here

Content warning – mental health

Sarah Hannah Milner was born in Sheffield in 1864 to Isaac and Sarah Milner. Her father was a merchant and a banker. Milner experienced a variety of mental health conditions and received care at the Retreat over several decades. The Retreat was founded in 1792 and operated under the principles of treating patients with respect and dignity, as well as Quaker philosophy. Milner loved spending time outdoors, and dedicated her life to helping other patients. She attended University lecture courses, as well as Quaker schools and meetings. Following her time as a patient at the Retreat, she continued to live there as a volunteer until her death in 1934. She provided care to female patients, worked as the librarian, and edited Harbour Lights, the Retreat’s magazine. She was the first editor of the magazine, writing an editor’s column at the beginning of each issue and covering wide-ranging topics, including religion, sports results, and congratulations on engagements. Outside of the Retreat, she was a long-term member of the Yorkshire Adult Schools Union, serving as president of both the local and county-wide Women’s Committees. The charity’s work included the education of women of all ages, as well as the provision of care to the poor and women prisoners. Sarah Hannah Milner’s story is that of a York woman who overcame marginalisation to advance the health and education of other women; an inspirational story that deserves the attention of the public.

Download Sarah’s research notes here

Winifred Naish née Rowntree (1884–1915) was the youngest child of philanthropist Joseph Rowntree and, as in tradition with other members of the family, was active in her local community. At 17, she established her own organisation in the Leeman Road area of York that aimed to instil honesty and kindness amongst its members, and provide entertainment and education for local girls. The Honesty Girls Club (1902-1940) catered for girls aged 5-25 or until marriage, offering weekly classes in a variety of areas, such as morris dancing, copper work and needlework. Winifred sat as president of the club from its creation in 1902 until her death in 1915, during which time the club’s attendees increased from 24 members to 200. Winifred lived in York her entire life, marrying in 1907 at the Friends’ Meeting House, and had three children with husband Arthur Duncan Naish.

Download Winifred’s research sheet here

Download Winifred’s presentation here

Ethel Maud Steigman[n] was a black and white photographer born to German immigrant parents. She presents as a person of interest in contextualising foriegn integration into the York community at a time of growing anti-german sentiment, and the growing photographic market that working class women were increasingly able to be a part of.

Download Ethel’s research sheet here

Download Ethel’s presentation here

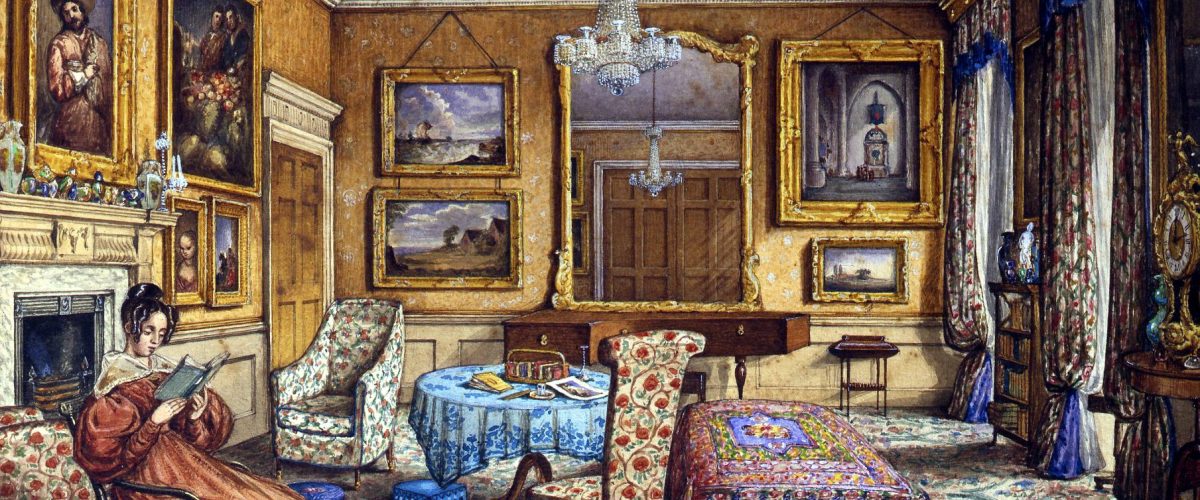

Mary Ellen Best was a watercolorist native to York who set up as a semi-professional artist in the city as soon as she left school. She would mostly find work through her social connections, she had a large social circle and so would be commissioned by friends and acquaintances.

Ellen did not stay in York her whole life, she had a passion for travel, and she embarked on several continental tours. In her work she often depicted women servants and working-class people.

Mary married a schoolteacher, Johann Anton Phillip Sarg and Ellen provided the main source of income from her inheritance, so her husband could be a “typical gentleman of leisure”. There was a drastic change in her paintings following her marriage- she stopped portraying herself as an artist and she often depicted her husband and children but seldom showed herself taking part in family scenes which could show she was unable to identify fully with her domestic role.

Download Mary Ellen’s research sheet here

Download Mary Ellen’s presentation here

Susanna Wells was a student and then teacher at The Mount Schools for girls. Susanna was a pupil from 1871-7 and was the first to attend university from the Mount.

At the school, there were four different classes, each class corresponded with ability rather than age, the first class was filled with the highest achievers on exams, and the fourth class held the lowest achievers. Susanna Wells occupied the first class, presumably for most, if not all, of her subjects during 1875-6. Susanna was also a “trainer” at the school, which therefore indicates her parents were not amongst the wealthiest Quakers.

Susie Wells and M.J.T had domestic/servant jobs because they were “trainers”, in 1875 they were ‘to keep the lavatory tidy and see that no hats, shawls, &c., were left about in the “corridor”, but hung upon their right hooks.’

Susannah Wells attended university at a time where most women were not entitled to an intellectual education. Most of the lower-class women learnt basic literary and religious skills, whilst middle-class women learnt accomplishment skills, such as art and music. Furthermore, without women like Susannah, women would not be able to attend university today, or at least not under the same circumstances.

Download Susanna’s presentation here

Violet Key-Jones was joint secretary, with Annie Coultate, later treasurer and finally official York organiser of WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union). Violet preferred militant tactics like smashing windows to show “an earnest spirit”. In February 1911, York’s suffragettes performed three plays in the Assembly Rooms which Violet acted in. Violet, her brother and Captain Ranson produced three plays in association with the Actresses’ Franchise League. This was formed in 1908 as a method of demonstrating support for women’s suffrage.

Violet, like many other suffragettes, evaded the 1911 census. It is thought that three to four thousand women protested through evading the census. Violet drummed support for the evasion and took on a leadership role as the organiser.

In March 1912, WSPU infiltrated an anti-suffrage meeting in the Exhibition Buildings with sufficient numbers to defeat an anti-suffrage motion when it was put to the vote (Violet was definitely there). She tied herself to a chair and had to be forcibly removed when heckling Keir Hardie and Philip Snowden (anti-suffrage politicians) in March 1913.

To help Harry Johnson escape detectives from a house in Heworth, Violet dressed Johnson as a woman and herself as a man to evade detection (this was one of the more militant tactics of the York suffrage movement along with the arrest of Annie Seymour Pearson in London).

Much of Dorothy Bleckly’s life followed a predictable course. Born in Yorkshire in 1775, she was a wife and mother for 26 years. While her husband was the typical breadwinner, Dorothy took on the role of caretaker, looking after her children and her household. Our research shows that Dorothy’s time as a devoted full-time mother was fairly typical of women in the Georgian period.

She had eight children over a 15 year period. Unfortunately one of her three sons passed away at a young age. Despite this loss, society placed an inordinate amount of pressure on women, expecting them to be fully dedicated to the raising of their children, an expectation that Dorothy largely fulfilled. However, after the sudden death of her husband in 1826, it is likely that Dorothy became overwhelmed by her grief.

While nineteenth century society mandated a practical fatalistic look at death, with a quick return to normal life, Dorothy, on the other hand, was heavily impacted by the loss of her husband. In this aspect of her life, Dorothy broke from the ordained course of life, becoming an anomaly compared to most other women of her period. This led to her admission to The Retreat, a York mental health asylum, opened by a local Quaker. Dorothy entered The Retreat in 1826 under constitutional circumstances, in the case of her first attack. This suggests a direct link between the death of her husband and the subsequent admission.

Download Dorothy’s research notes here

Content warning – sex work and abuse

Elizabeth Frowe lived and worked in York in the early fifteenth century, specifically around 1409. She was involved with sex work within the city, probably in Goodramgate, where much of York’s medieval sex work occurred. Joan Plummer, another sex-worker mentioned alongside Elizabeth in The Dean and Chapter Act Book, is stated to have worked in Goodramgate, and the close working relationship between these women would identify that Elizabeth also likely worked there. She had close links with the Augustinian clergy in York, procuring prostitutes and working as one for their benefit. Naturally, as this involves the church, records on this are few, but The Dean and Chapter Act Books in the Borthwick

Archives provided us with evidence of this co-operation. It is rare to find a woman of low status mentioned in medieval archives, let alone religious ones, especially as she was mentioned alongside another woman, which shows the plurality of York’s sex work in the fifteenth century. Through researching Elizabeth Frowe, a more personalised approach to medieval sex work in York can be formed, something which leaves its mark on the city to this day. There is a gap in historiography for sex workers specifically involved with the church, and the case of Elizabeth Frowe is particularly salient because it illustrates the relationship between the church and their community, whilst also provoking conversations around the moral integrity of those who had such a central role in the religious lives of lay people in York.

Download Elizabeth’s research notes here

Content warning – infanticide and mental health

Born in 1779, Mary Thorpe was like any common woman. She became a servant at age 14 and lived a simple life as a respectable young lady. This was until around the age of 20 when she fell pregnant and was abandoned by the father of her child. 11 weeks prior to her due date, Mary left her service and went to Sheffield to stay with a widow by the name of Mrs Hartley who assisted with the birth of her child. In December 1799, after some days of caring for the child, she fell ill with ‘milk fever’, a sickness which made a woman delirious. She took her child to a pond and threw the child into the water, where he drowned. Mary’s defence centred on her suffering from milk fever, claiming that though she was guilty of the crime, she was ill and delirious when committing it. Despite this being a proven fact, Mary was sentenced to death as it was believed her milk fever did not make her unaware of her actions as she had taken premeditated actions such as lying about taking the child to be baptised with her sister when he was killed and supposedly lying about her son’s existence to Sheffield Constable Hill. However, during the trial, she showed much guilt, and for lots of women who committed infanticide, they often did it for many reasons, most times not in cold blood.

Download Mary’s research notes here

Initiated by Social Vision. Hosted by York Museums Trust